This short story appeared in my author newsletter in September 2024. You can read it on Mailchimp here, and sign up to my newsletter here

We lived in the mailroom, moles with blunt nails and teeth. They taught almost every subject at the University and my supervisor,George, claimed to have learned most of it.

Campus I rode on the mailroom bike, delivering whichever of the mail had the right address, which was far from all of it. It was a big place. History, Physics, Mechanical Engineering, Music, Sculpture, Mathematics, Student Welfare, Counselling, Modern Languages, Classics. I won’t go on. Medicine. The campus was too large and the buildings too complicated. Some of the departments you could only enter through a back door. In my first six months I’d got lost quite regularly. After two years I still did, so there was no hope for the mail.

Administrators and academics sent all sorts. Letters, phone chargers, geology samples. Scraps of embroidery. Video and audio tapes in obsolete formats. Once, an internal memo with “I love you” scrawled on the back. We weren’t supposed to open things, but sometimes there was no reason not to. So much of it was so wrongly addressed it never would have found its way home.

Professor Alan Mack’s birthday card had come back to us for the eighth time, returning with a new scar, bleeding glitter all over my fingers. Seven people had written across its front: Not Known In This Department.

My supervisor George was a human rabbit of a man. Big ears, whiskers. “That card needs to go inthe bin,” he said. In July, the place emptied out, and there wasn’t much to do, apart from sorting out the shelves. We could sit on the lawns, pretend we were there legitimately, enjoying the sun and getting paid for it. George let me come in late and leave early. There wasn’t enough to do to make coming in for a full day worthwhile.

“Why?” I said. For me, finding Professor Mack had become a game. Somebody who didn’t have his home address was trying to wish him all the best. Somebody from a conference, maybe. The academics went on these jaunts. Some were hosted at our place. Every January there was a jousting festival. A guy came with a jerkin and some buzzards, which he fed meat on the Union steps.

It was no use looking on the website. The staff pages were hardly ever updated. “I’ll find him eventually,” I said. “You watch.”

The shelves, the Lost Shelves, looked like something out of a documentary about hoarders. Letters and envelopes shoved together like the cards of a flower press. Unopened parcels from M&S and Toast, things the staff had had sent to work, but which had been misaddressed and had ended up down here. There were a load of books from book suppliers and academic publishers, for which George had a terrific nose.

“Here’s one for you.” He took one out of its cardboard sarcophagus, handed it to me. “This is right up your street, isn’t it?”

The book was titled Feminist footnotes: re-reading correspondence from England’s forgotten women letter writers, 1724-1792. It was hot, post-exam celebrations over and done with, campus deserted. Rabbits colonised the quad lawns, twitching wide-eyed and whiskered in places where undergraduates normally gathered. George and I had opened the big doors to the sorting room but it was still dark, deep as a sunset, dust motes swirling. “You might as well have it. There’s probably a copy in the University library anyway.”

Funny, I’d always thought I’d come back to university, and here I was. During term time, I rode around campus on the mailroom bike wondering how everybody, even the first years, seemed to know where they were going. My time at university hadn’t been like that. I’d arrived lost and stayed that way. Knowing where to sign up, where to go for this lecture, that seminar, how to sign up for modules, which day and time to go to library induction, working out how many credits you needed, which bits of the course were compulsory, all the different dates for signing paperwork for student loans, bank accounts, uploading coursework to the e-portal, there was so much of it, and I couldn’t keep track. They’d put me in a houseshare with eight strangers, in a room at the top of the house with a puddle shaped stain on the ceiling which dripped onto the bed. Nobody else had wanted this room, which was why it was less expensive than the others, but still pretty bloody expensive.

There seemed to be an extra person living in the house, somebody nobody had invited, a person who crept the stairways and halls at night and opened doors with a creak, peeking in through the gaps. I could never tell whether I was in the house alone, and hated being there, but I didn’t know my housemates well enough to knock on their bedroom doors for help. At Christmas I’d left, leaving most of my stuff behind, and had never gone back.

I delivered letters and other things there now. The administrators, blank-faced, dark-cardiganed, in the department where I’d once studied, took the mail from me without even looking at my face. Even if they had, I doubt they’d remember me. I’d not even made it to the end of term.

Thank you for reading

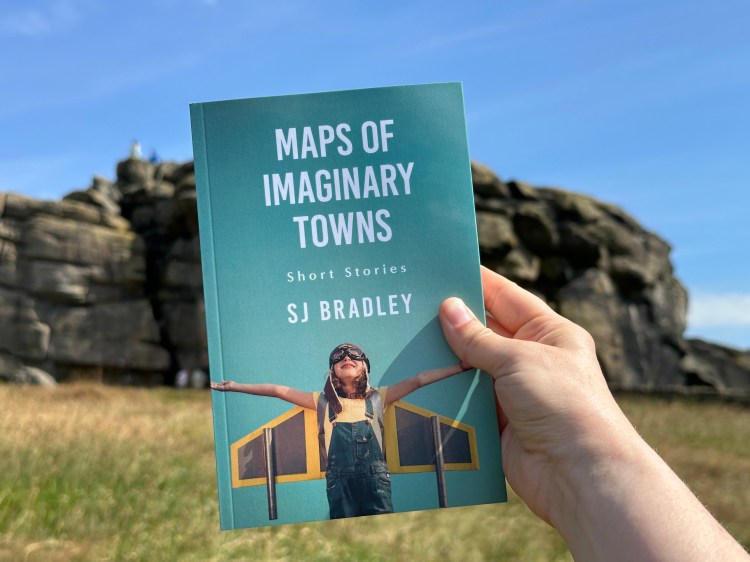

The above is an excerpt from ‘Dead Letters’, from my new book Maps of Imaginary Towns, which is available now in all bookshops.

If you’re in Leeds, you can buy the book in Holdfast Books – an independent bookshop on a barge moored near the Royal Armouries; in Books on the Square Otley; in Waterstones, and it will also soon be available to borrow from the Library. It is also available as an audiobook on Audible here.

fabulous. And Guest is magnificent.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Paul! I’m glad to hear you enjoyed Guest and Maps of Imaginary Towns. All the best, SJ

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s the first story in ‘Maps..’ and it set a high bar which you nailed with every subsequent tale. I was given ‘Guest’ as a Christmas present and loved it. Thanks.

LikeLike